Breaking Frontiers

By Maliha Masood

Observing weapons bazaars, smuggling routes, and endemic corruption first hand, Maliha Masood uses her Pakistani passport to travel the Khyber Pass to Afghanistan's border.

The bazaar in Landi Kotal is a gunsmith's paradise. An impressive display of Kalashnikovs and AK–47's, pistols and hand grenades. I ask one of the merchants if he still has the Stinger missiles that the CIA supplied to the Afghan Mujahideen resistance. "They were brave men," he says. "They fight Russians for USA."

A nasty cough ripples from his lungs and then the merchant draws my attention to an authentic Chinese assault rifle. Would I care to see the famous Israeli Uzi sub machine gun? He also has some old Enfield .303 rifles.

"From India," he points out. "Indian woman very beautiful. I watch movie on VCR."

I lead him back to the question of Stingers, many of which were unused after the Soviet withdrawal. The United States government had spent vast amounts of time and money to recover the surface to air missiles, but the covert nature and lack of oversight of arms shipments made it virtually impossible to keep track of what happened once the weapons left American hands and were funneled into Pakistan.

"My friend in Dara," the old merchant says. "He have. Many people buy to fight war in Kashmir."

I turn down his request to see his collection of revolvers. Apparently, he's quite proud of the local knockoffs of the .32 caliber Webley. They're made by a factory in Peshawar, where you can also buy top quality hashish. He can get me some smuggled stash from yet another friend.

Landi Kotal is an old garrison town, dating back to the days of the Raj. Crumbling watchtowers and insignias of various British regiments still guard this highest point on the Khyber Pass. We drive slowly through the cantonment, past the barracks and the Khyber rifles mess. The driver pulls into what appears to be a spacious guesthouse and salutes a slew of approaching servants. Anwar leads me into a tasteful salon decorated with ethnic handicrafts and black and white photographs of former VIP guests. I recognize Prince Charles, Nehru, Jinnah, and the Malaysian Prime Minister Mahatir. After washing up, we settle down to a meal of daal, chappati, bhindi and mutton pulao strongly flavored with cardamom.

The Pashtun wait staff hovers around Anwar and I, clearly not accustomed to serving such insignificant company. The two of us sit around a huge teak table that can accommodate at least twenty. Anwar eats quickly and elapses into an awkward silence, eying me furtively from time to time. Despite his friendly chatter on the drive, I sense his discomfort in my presence. Underneath his brandy and cigar exterior, he conceals centuries of Rajput blood that has neatly divided the world of men and women into two separate chambers. I am clearly breeching protocol. Nonetheless, Anwar has turned out to be a good host, a friend of a friend whose gracious welcome has given me courage to leave the boring confines of Islamabad for a weekend on the Khyber.

Into the Khyber Pass

The drive up the pass is nothing short of spectacular. We cruise through what looks like a moonscape of dung–colored hills. For a moment, it feels as if I'm airborne, witnessing sharp angles of earth and sky. The road hugs a series of tight switchbacks. In the back of a Land Rover, I slide from left to right on the vinyl seat like a stray hockey puck. Visions of invaders and conquests dance through my head. The Great Alexander, Mahmud of Ghaznavi, Genghis Khan. Men, armor and horses. They were all here.

During the 1980's, the world's most famous pass was inaccessible to all but journalists and aid workers given the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. I learn that the Khyber, which is part of Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal Areas, is officially closed to foreigners at this time. Since I have a Pakistani passport, a Political Agent has given me permission to travel through.

"He is a very nice man," Anwar says. "We studied at Qaid–e–Azam University together. He also has a Master's in IR."

A Political Agent, Khyber Pass and the Tribal Areas. This I couldn't wait to see. Entering Khyber agency at the border outpost of Jamrud, a marble sign acknowledges the infamous Alexander, known to locals as Sikandar. As the SUV climbs up the looping road, a man pedals furiously on a bicycle with three more trailing behind. Anwar points out the cycle smugglers who are paid 200 rupees for each made–in–China bike they transport from the Afghan border into Peshawar, a distance of roughly sixty harrowing miles. It's a thankless job, risking not only flat tires but also head on collisions and avalanches on an average day's work. Thanks to the poor man's mazdoori or labor, those same bikes fetch up to 3000 in the Rawalpindi bazaar.

Anwar is full of interesting tidbits. He talks about the notorious corruption along the Khyber. Imported goods shipped from Singapore, Malaysia, and Japan to Karachi port are loaded onto trucks for transshipment to Kabul, about a thousand miles away. Upon reaching the Afghan border, the refrigerators, AC's and TV's are unloaded and smuggled back into Pakistan.

At every checkpoint, bribes substitute for customs duty. Prosperous smugglers and drug barons have built huge villas just outside of Peshawar, complete with manicured gardens, marble entry halls and a private militia of armed bodyguards. Anwar expounds on his pet theory that the tribal beltway is one of the safer parts of the country. The lack of rigid laws gives less incentive to break laws. Justice is a private concern. For the most part, people are just trying to get by, eking out a living the best way they can, even if means selling drugs and weapons.

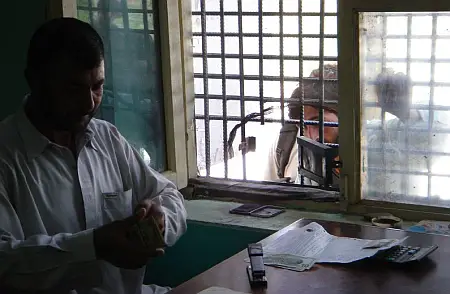

Flickr photo © Goosemountains

The Political Agent

"Afghanistan is waiting!"

I am staring at a tall, dark–skinned man with a mile long grin.

"Tayar ho?" he asks if I'm ready to go.

Back at the guesthouse, I finally meet Abdul Ghafoor Shah, the local Political Agent who has given me the green light to come this far. We sit down for some tea and lemon cookies in the garden. I want to ask Ghafoor about his job, but he keeps teasing me about my low intake of sugar and dumps three heaping spoonfuls into my chai.

"You need to put on some weight," he pronounces definitively. "How can you climb mountains looking like that?"

Ghafoor is probably in his mid thirties though he looks much older. Clear hazel eyes radiate warmth, making the rest of his heavy–set features less foreboding. I like the way he laughs, rocking back and forth and clutching his stomach. His easygoing manner immediately strikes a friendly chord. We carry on a running commentary about our love of mountaineering. Ghafoor recounts his adventures in Chitral. I can almost picture tiny exclamation points dancing in his pupils.

"The Kalash are a very interesting people," Ghafoor says. "They did not convert to Islam so they are considered kafirs living in Kafiristan, the land of non–believers. What nonsense! I have many friends there and they are good kind people. And you should see the women. They have long hair up to here," he touches his hips. "And they wear shells in their braids, like your Native American Indians."

"Are you sure about that?" I ask. "I thought they wore feathers. I don't remember any shells."

"Shells, feathers, it's all the same!"

"Yes indeed."

"So will you take me to Chitral?"

"Well, you'd better fatten up those skinny shoulders first!"

Ghafoor laughs and dumps more sugar in my cold tea.

I try to include Anwar in the conversation, but he sits in a corner and sulks, unable to compete with Ghafoor's easy banter. All of a sudden, my newfound acquaintance gets up and bids me salaam.

"Excuse me, but I have to go extend a ceasefire," Ghafoor announces with a grave expression.

I ask the Political Agent what he'll offer as incentives.

"Oh you know, the usual carrot and stick approach," replies the PA and hurries off to strike another deal.

Twenty minutes later, he is back in the garden. We take Ghafoor's jeep and drive towards the Afghan border. His three bodyguards trail behind in a separate vehicle, making sure to maintain a respectable distance.

Copyright (C) Perceptive Travel 2009. All rights reserved.

- Unbalanced in the Sinking City by Tim Leffel

- Lost in the Mangroves of Belize by Steve McNutt

- World Music Reviews

Books from the Author:

Buy Zaatar Days, Henna Nights at your local bookstore, or get it online here:

Amazon US

Amazon Canada

Amazon UK