Lionfish Hunters of Tom Owen's Caye

Story and photos by David Alexander Baker

When a father sees the coral reefs disappearing faster than his daughter's childhood, he books a trip to a remote island in Belize for the two of them to become hunters of an invasive fish.

My daughter drifted up to the fish with her arm extended, gripping the sling-spear near its forked tip. The rubber loop affixed to the butt end and hooked around her thumb was stretched, the contraption loaded with tension. The fish, the size of a cantaloupe, was achingly gorgeous, candy striped and trimmed in ribbons of fins and venomous spines. It hovered with indifference above the grooves of a giant brain coral. Maybe it sensed the novice hunter was an uncertain shot. Maybe it felt secure in its pincushion armor.

But arrogance was its downfall. Bailey released her grip. The spear flew, skewering the fish, which unspooled threads of blood into the water. She'd found her first victim. The other divers pressed their hands together in underwater applause.

We'd come to Belize to kill fish and save corals. One of the most beautiful creatures on the world's second longest barrier reef also causes the most damage, so Bailey and I had joined a strike team of spear-wielding conservationists on lethal expeditions to deep coral canyons in order to hunt down these lovely fish.

And eat them.

In this way we learned that conservation could be both delicious and fun. Especially when your base of operations is a tiny jewel of an island set in gradients of Caribbean turquoise, fully equipped with a dozen hammocks, a volleyball net, and a professional chef.

Dad and a Teen Head to Belize

This adventure had begun years before, when I'd first started diving on coral reefs for my documentary film work. My daughter, then ten, tried on my dive gear. She wandered around the house in fins with my wetsuit accordioned down to fit. "Take me with" you," she'd say whenever I packed for the next assignment. She wanted to learn to dive. I told her I'd bring her one day.

But the years slipped by with that promise unfulfilled, and suddenly she was seventeen and no longer asking to tag along. She was choosing a college and preparing to flee the nest. What's more, healthy coral reefs have grown increasingly rare. More than half have disappeared due to human pressures; the news is filled with a daily drip of declining reefs.

That's when I came across a program in Belize called Reef Conservation International. They offered five-day trips to a remote island where volunteers paid for the opportunity to learn about reef ecology, participate in underwater conservation, and even check off training requirements with certified dive instructors. What's more, the tiny island measured less than two acres and lacked WiFi. With glimpses of my daughter growing rare as sasquatch sightings, it promised few places for a teenager to hide.

So that's how we wound up, after a redeye flight from Oregon and a gauntlet of airports punctuated by a jouncy ride in single-prop island hopper, standing on a dock of Hokey Pokey Water Taxi at the end of a sandy finger of land pointing south toward Honduras, waiting for a boat to take us to speck of an island known as Tom Owen's Caye.

It took an hour of slamming through large waves on the inner lagoon to reach the tiny island. As we pulled up to the dock, we could see a line of foam rippling out to the horizon as swells broke on the shallow shelves of the vast reef system.

We were now on the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef, a feat of coral construction second only to the Great Barrier Reef. It runs seven hundred miles from Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula, along Belize, past Guatemala, and down to Honduras. It's the home range of one of the largest surviving populations of manatees. Hawksbill and loggerhead turtles nest there. Whale sharks stop by for visits, along with five hundred other species of fish. There are also 65 species of stony corals, tiny colonial animals that are the architects of this enormous structure.

I was pleased that there were other parents with teens in our group. An early fear was that my daughter would be marooned with conservation-minded travelers my own age. But as our mixed group disembarked, we wandered the little island charmed and awestruck. Palms swayed above, many strung with hammocks. A half-dozen huts and a sturdy central building with walls of mortared reef rubble seemed both cozy and comfortingly hurricane proof. There was a volleyball court, a makeshift outdoor gym, and then what looked to be a cheerful little cemetery, but upon closer inspection was a collection of signposts and conch shell rings indicating where sea turtles had recently nested.

And then the bell rang. It hung in the courtyard of the main building. We assembled for our first briefing, where we received our room assignments and learned the rules of the island—mainly that when the bell chimed, you came running. It would summon us to collect our dive gear and load the boats for our early morning dive. Then it would muster us for breakfast. Next it gathered us for presentations on reef conservation, coral biology, or fish identification. The cycle would repeat for more dives, meals, and presentations. The bell kept us on schedule. It roused us from hammock slumber, swimming, reading, or sitting on the edge of the pier soaking up nature. The bell is what saved us from the indignity of being ordinary tourists. It transformed us from visitors into volunteers.

We were an easygoing, compliant bunch, though it's admittedly not difficult to encourage compliance when the most demanding task was a five-minute boat ride to spectacular dive sites. Or a graciously prepared and attractively plated meal by the resident chef, Bol, who proudly welcomed guests to his table with a personal description of each dish. An army marches on its stomach, and though we were an army of students, writers, teachers, teens—plus a professional dolphin trainer and a union pipe-fitter—we were molded over the week into a trained and not-so-elite fighting force.

The Lionfish Hunters on Patrol

We weren't killers. Politically, we leaned largely as a group toward granola. But after training on land with sling spears and unsuspecting coconuts, we were ready for battle. We prepped and loaded our dive gear. We sped out to the theater of action, rap and reggae blaring on the boat speakers, the teens and dive leaders bobbing their heads. Sam, one of the divemasters, called orders to the boat pilot in creole, and as the captain pulled back on the throttle we eased to a drift. Our leader stepped forward and gave us the briefing, describing the site and the depth, the sunken features, currents, and direction we would be swimming. He reviewed the hand signals.

"Our mission on this dive,” he finished, "is to kill lionfish.”

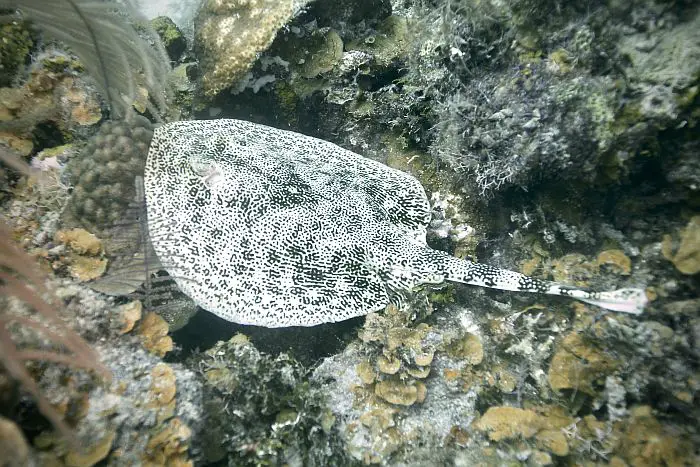

Pterois volitans, also known as the red lionfish, is voracious, beautiful, fecund, merciless, and tasty. In Belize, and everywhere else in its expanding range in the Atlantic and Caribbean, it is invasive. Lionfish exist in a baroque, feathery cloud of their own fins and venomous spines. Their orange and red stripes both call attention and also make them difficult to spot against the varied topography of the reef bottom.

Pterois volitans, also known as the red lionfish, is voracious, beautiful, fecund, merciless, and tasty. In Belize, and everywhere else in its expanding range in the Atlantic and Caribbean, it is invasive. Lionfish exist in a baroque, feathery cloud of their own fins and venomous spines. Their orange and red stripes both call attention and also make them difficult to spot against the varied topography of the reef bottom.

Hailing from the Indo-Pacific, lionfish made their Atlantic debut off the coast of Florida in 1995 and from there spread quickly through the Caribbean. How these Pacific predators made the leap to this side of the world, nobody knows for sure, but it's fairly certain that they had human help. And they can bring down entire ecosystems.

Red lionfish are lethal predators. They'll eat anything their own size or smaller. And because larger predators in the Caribbean have not evolved to work around their eighteen venomous spines, and because their prey species have not adapted to evade them, lionfish and their insatiable appetites are the perfect killing machines. They'll snack on anything from juveniles of commercially important species like grouper and snapper or those that perform the vital task of reef algae removal, like surgeonfish and parrotfish. They can decimate coral reefs and put fishing communities out of business. They also reproduce at a rate that puts rabbits to shame, producing up to two million eggs annually.

So given their fecundity and ferocious appetites, hunting lionfish didn't seem like some lark or novel greenwashing. It was serious work. Every dead lionfish removed from the reef reduced a coral reef threat.

While I was skeptical that a squad of newly trained spearfishers could make much of a dent on lionfish populations, each dive leader optimistically carried two sling spears and a thick collecting tube into the depths on every dive. And we usually encountered our first lionfish within minutes of slipping below the surface.

Given the scale of their impact and their fierce reputation, lionfish are surprisingly easy to kill. While it does take skill to learn how to work a spear underwater as you control your buoyancy and avoid stabbing yourself or another diver, lionfish patiently await their coup de grâce.

They're often found in hunting groups of three or more, drifting near the bottom or edges of large corals where they use their fin-inflated profiles to herd shoals of juvenile fish, slowly surrounding them before sucking the fry into their massive mouths with lightning-quick gulps. It's unsettlingly easy to sidle up to a lionfish and ready your spear.

When someone in the dive group spots a lionfish they'd wiggle interlaced fingers to alert the team. The dive leader hands a spear over. The appointed hunter then loops the elastic band around a thumb and chokes way up on the spear, stretching the band, gripping the shaft six inches behind the tip, loading the sling with tension. The hunter drifts up close to the fish, within two feet, extending her arm and waiting for a clear shot.

I felt bad the first time I speared a lionfish. They're pretty, and I felt the vibrations of the death throes running down the spear shaft to my arm. Stuffing the expiring carcasses into the tube filled with lionfish carnage also seemed cruel and brutal. But I quickly got over it. My Pleistocene instincts took the helm and I became a hunter, immediately scanning for the next fish. By my third kill, my tree-hugging, animal-loving tendencies were buried beneath a newfound aptitude for butchery.

Lionfish on the Dinner Table

After every dive, we returned with dozens of dead and dying lionfish. There was a demonstration table by the pier, and a popular activity, especially with the teenagers, was cleaning the lionfish. Each specimen, no matter how tiny, was carefully fileted, with extra care taken to avoid the venomous dorsal spines. A sting can be painful though not fatal to humans. The average filet was bite sized, about as big as a chicken nugget.

Every day, ten of the unlucky invaders suffered the added indignity of dissection. Their stomachs were sliced open and the contents were picked, prodded, and logged on a spreadsheet, noting the numbers and species of undigested prey. And at night, our talented chef served up the filets fried or in curries. The meat has a dense texture, soft and rich. Locals compare it to grouper, a fish so tasty that the signal you use underwater to indicate that you've seen one is to rub your tummy and smile.

Throughout the week, our team grew more deadly with our spear work. I no longer felt a twinge of guilt when I impaled a lionfish. The daily kill tallies climbed. And as the new trainees gained confidence in their diving and joined more advanced divers in the open water, they earned their chances.

By the time we left the island, my daughter had earned her certification. She'd become a confident diver. And she had two confirmed lionfish kills. I couldn't be more proud.

Ecotourism and Our Ailing Coral Reefs

I wondered how much positive impact our team of novice lionfish hunters might have, but the program has been hailed in the Belize National Lionfish Management Strategy. Reef Conservation International harvests between 4,000 and 10,000 lionfish each year. They study the stomach contents of 40 fish per week and share the data. After a spike in lionfish populations in Belize occurred shortly after they first appeared, their numbers have declined and leveled off. There's little doubt that our efforts reduced a direct pressure on the reefs.

Killing lionfish was so much fun that it wasn't until our last day of diving on the island that I looked closely at the coral cover on the massive outer slope of coral structure that faces the open sea. Much of the intricate, coral-built rockwork on the slope was just bare skeletons, the living tissue gone. A few colonies grew here and there on the ghosts of massive coral heads.

A recent study found that only 17 percent of historic coral cover remains on the Belize Barrier Reef, and that estimate matches what I saw on that last dive. There were thickets and patches of lush coral cover around our little island and in some of the coral canyons, but it was clear that, overall, this was a reef that was fighting the same battle for survival as those the world over.

So I left Tom Owens Caye with mixed emotions. Killing lionfish was necessary work. The program was part of a solution. The work we did was certainly better than sitting on a developed shoreline sipping daiquiris. I was glad that my daughter was able to learn how to dive. But I was worried about the coral cover. I wished for more hope than 17 percent coral cover could provide. I found a dash of that hope on our little Caye.

Ecotourism is still tourism, and it carries all the ecological baggage of international travel. It probably won't lead to the salvation of reefs. Perhaps it is only moderately less damaging than other forms of tourism, but it feels like a step in the right direction.

One night on Tom Owen's Caye, a female turtle dragged herself up onto the island and painstakingly began digging holes, prospecting for the perfect spot to nest. Well past midnight, we stood sleepily watching the mother turtle search for just the right spot. One of the Belizean guides steered the tired turtle away from the volleyball court and other high traffic areas as she searched like Goldilocks for the ideal spot to nest. Weary from diving, most of us eventually drifted back to our rooms. The next morning a volunteer told me that she had stayed up to watch the turtle lay seventy-eight eggs in the wee hours of the morning. There were tears in her eyes as she recalled how the weary turtle covered her nest and dragged her heavy body back toward the sea, trusting us with her secret. In her recounting of the event, I saw the power and potential of ecotourism to bind us to wildness, something we sorely need in our hyperconnected lives.

There's good research that shows exposure to the natural world can improve our physical and mental health, relieve stress, reduce fatigue, enhance our mood, and even help us live longer. And while we need nature, we need each other more. That's what the acre and a half of Tom Owen's Caye achieved. It threw a group of neophyte lionfish hunters together for a few days in a far corner of the world and knit us together in unified awe at the wild world around us, and in the human community that had suddenly formed there in the heart of the middle of nowhere.

Wildness had assembled us. Many in our group had been in transitions of disruption. I was mourning the fact that my daughter would soon be leaving home just as her firewall of adolescent independence was beginning to soften. I'd also been mourning the anthropogenic changes that had been driving the loss of coral reefs around the world for years just as she was discovering their wonder.

There were guests who were changing jobs and beginning and ending marriages. There was a woman who'd left a dying dog at home and another man who still mourned the dog he'd lost years ago. Nature is a tonic for past and present tragedies. There were teens just about to leave home for college. And there was a recent college grad desperately delaying adulthood. All of us stood at the crossroads. We all understood how precarious was this landscape that surrounded us. And all of us had come to Belize for the same reason—to be immersed in wildness. To be remote. Isolated. And to be together.

David Alexander Baker is a writer and filmmaker based in Oregon. His work includes the novel Vintage and the film Saving Atlantis. This is an adapted excerpt from the book The Lost Continent: Coral Reef Conservation and Restoration in the Age of Extinction. Copyright © 2022 by David Alexander Baker. Used with permission by Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc. All photos by the author.

Related Features:

Kayaking Around Specks in the Ocean in Belize by Tim Leffel

Showdown at the West Esplanade Canal by Darrin DuFord

Seeing the Great Barrier Reef Before It Dies by Michael Buckley

Bringing Coral Reefs Back From the Dead by Jeff Greenwald

See other Central America travel stories in the archives

Copyright © Perceptive Travel 2022. All rights reserved.

- Evolving Views of History at the Whitman Mission Historical Site by Teresa Bergen

- Looking for Home in a Coffee Growing Paradise in Colombia by Julia Hubbel

- Freak Shows and Farces at the Ringling Circus Museum in Sarasota by Tim Leffel

- Travel Book Reviews by Susan Griffith

Books from the Author:

Buy Vintage at your local bookstore, or get it online here:

Amazon

Amazon UK

Amazon Canada

Kobo Canada

Buy The Lost Continent: Coral Reef Conservation and Restoration in the Age of Extinction at your local bookstore, or get it online here:

Amazon

Kobo Canada